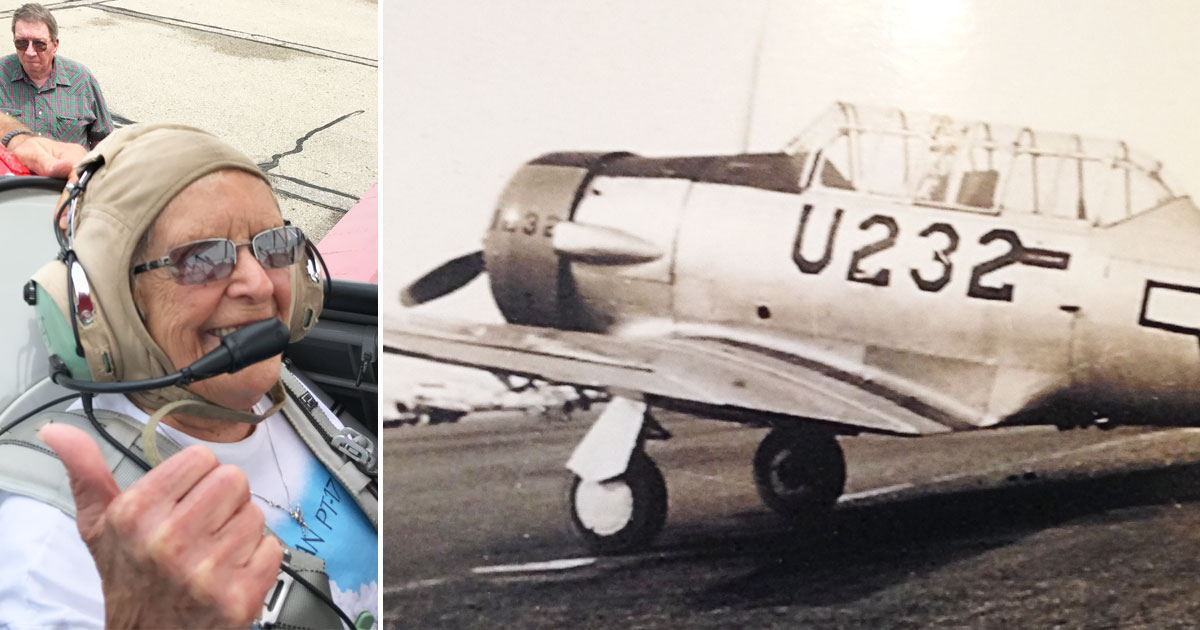

On July 12, 2017, Ageless Aviation Dreams Foundation (AADF) flew into Grand Rapids to honor eight military veterans and military spouses who live at Covenant Village of the Great Lakes. AADF is a nonprofit organization with a mission to give back to those who have given, by providing flights in fully restored Boeing Stearman biplanes—the same aircraft used to train aviators in the 1930s and '40s.

That morning, Jane (Baessler) Doyle took to the skies.

Again.

In the years preceding and during World War II, the United States government had a glaring need for more civilian pilots. Beginning in 1938, the government sponsored a Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) at flight schools and educational institutions across the nation.

"For every 10 men, they'd take one female," Jane said.

And she was one.

Jane was 6 years old when Charles Lindbergh flew into Grand Rapids and aviation first captured her attention. At age 18, it stole her heart.

"The first time up, I thought I was in heaven."

Jane earned her private pilot license in 1940, and kept up her flying time through the Civil Air Patrol while studying interior design at the University of Michigan. Her brother asked her to join his architecture firm in Detroit once she graduated.

"But I wanted to fly."

Early in 1942, Jane received a notice inquiring if she was interested in joining the Women Airforce Service Pilots, WASP, a paramilitary aviation organization championed by Jacqueline Cochran that employed qualified female pilots for noncombat missions, freeing male pilots for combat roles.

Of the 25,000 women who applied, only 1,830 were accepted.

Fewer still earned their wings.

Jane moved to Sweetheart, Texas, for basic training and became one of the 1,074 graduated WASP members. Nearly every day for seven months, she rolled up the legs and sleeves on her zootsuit—all the uniforms were coveralls leftover from male cadets who had lived on the base—and reported to the flight line. She attended physical training and ground school for navigation, communications and maintenance. She learned how to fly aircraft from the BT-13 to the AT-6.

"We had to do loops and spins and rolls—all those things."

Jane and her classmates barely left the base, though sometimes their superiors carted them into town in a cattle truck. Despite the little time they had to spend with each other outside of physical training and ground school, Jane and her classmates became close. When one of her close friends was killed in a mid-air collision a week before graduation, they all felt the loss.

Jane was stationed in Seymour, Indiana, from 1943 – 1944. She worked in the engineering hangar, where her main duties included testing aircraft after engine changes, or when cadets found something wrong. Other times, she performed administrative tasks, such as transporting nonflying personnel to other bases.

She also met her check pilot.

"I hated him," she said. "He was strict."

His name was Don Doyle, and she married him. Jane resigned from WASP in 1944, after hearing the organization would be dissolved by the end of the year. Don remained in the service, however, and the two moved wherever he was stationed. Eventually, they landed in Grand Rapids with their five children. Jane focused her attention on both motherhood and work—first as a teacher assistant, and then as a team member on various projects in West Michigan.

Jane and other WASP members pioneered the airwaves for women to join the air forces, yet were never honored as military members during their service. Jane remained a civilian pilot until November 1977, when the United States government finally granted military status to all female WASP members.

Today, at age 93, she's a proud WWII military veteran—though her legacy extends far beyond military ranks. Jane tenaciously quilts for cancer patients, is a gifted painter with works previously sold in galleries, and has 12 grandchildren and 14 great grandchildren.

On the ground and in the air, she's still flying.

Written by Cassie Westrate, staff writer for West Michigan Woman.